After an extended break, our look at the world of video game culture is back! Kieran Mathers takes the new look Lara for a spin…

After an extended break, our look at the world of video game culture is back! Kieran Mathers takes the new look Lara for a spin…

This month saw the return of the venerable old lady of computer gaming. No, I don’t mean Samus from Metroid Prime. Crystal Dynamics have released the much anticipated Tomb Raider reboot, starring one Ms Lara Croft.

A lot of virtual ink has been spilled over this gritty story of Lara’s origins, mostly relating to its occasional gameplay flaws and restricted camera control. The bold re-casting of Lara has firmly split online opinion, with some believing it to be the boost the series needed, while other say that this new approach has ruined a character from the early years of 3D gaming.

I’m not going to engage with the gameplay debates, or the arguable over-use of Quick Time Events. Reviewers better than me have tackled those at great length, and I’ll only mention them when relevant. I’m going to look at Tomb Raider 2013 for what it espouses to be: a re-invention of Lara Croft, the icon and the woman. Have these radical changes ruined or saved her?

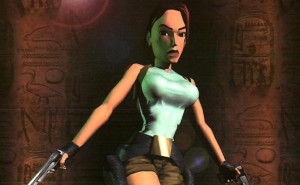

Lara Croft was born in the original Tomb Raider, all the way back in 1996. There are a lot of potentially apocryphal stories relating to her creation, including how the game was originally meant to feature a male protagonist.

Originally conceived to bring the 2D platform game, such as Metroid or Prince of Persia, into the 3D gaming environment, In truth, the original Lara could barely be considered a character at all. She hardly spoke, apart from grunting as she climbed or screaming as she fell, and the story revealed very little about her, the principal plot being find tomb, raid tomb. (The Nineties were a simpler time).

Originally conceived to bring the 2D platform game, such as Metroid or Prince of Persia, into the 3D gaming environment, In truth, the original Lara could barely be considered a character at all. She hardly spoke, apart from grunting as she climbed or screaming as she fell, and the story revealed very little about her, the principal plot being find tomb, raid tomb. (The Nineties were a simpler time).

She had attributes – guns, skimpy outfits, ludicrous breasts – but these didn’t constitute a personality. Early Lara was nothing more than the player’s avatar in the game world with no characteristics of her own.

It was only in the later games that Ms. Croft, now the centre of a hugely successful franchise, developed a personality and back-story. Her family was wealthy and she raided tombs for fun and profit, getting entangled with international crime syndicates, supernatural happenings and, most memorably, a dinosaur.

Through all this, she quipped and joked while gunning down assassins and wild animals, effectively becoming a female James Bond. In later games, such as Tomb Raider: Legend, she gained a support team and a butler (memorably played by Chris Barrie in the 2001 film). But the basic image of jumping, leaping, duel pistol-wielding Lara has remained virtually unchanged. Until now.

In this new reboot of the franchise, Lara is a student, travelling with a team of other archaeologists in search of the fabled island of Yamatai and its lost civilisation. Sailing into a sudden storm, Lara is shipwrecked on the island and separated from her companions. Weak, scared and alone, she must fight to survive the hostile inhabitants of this island and escape with her friends, solving the mystery of the Queen of Yamatai as she does.

For the first time, Lara is a real person. She falls hard, she screams, she reacts realistically to the environment and she gets scared. Her treatment is occasionally so tough to watch that the game has been accused of being ‘survival porn’. The fact that you are not always in control of Lara has annoyed a great many gamers, but it’s a conscious creative decision that allows the game to put Lara in situations where doubt, fear and pain can be clearly demonstrated. Seeing Lara struggle is crucial to identifying with her, as she takes the first steps on her hero’s journey. At last we have Lara Croft the woman, not the avatar.

I wish I could say the same about the support characters; a mix of dull archetypes that I assume principal writer Rhianna Pratchett didn’t work too hard on. (If she did, I suggest she has a chat with her Dad about characterisation). And yes, the balance between Quick Time Events, cinematics and gameplay could also have used some more work.

More strikingly, Tomb Raider suffers from a case of cognitive dissonance when it comes to the combat. It is spectacularly violent at times, including some kills with an ice-axe that are utterly brutal. The regularity of this violence badly undermines the vulnerability of Lara. She moves from being tearfully distraught at her first kill to gunning down seventy or more people just a few hours later. There are some wonderful moments inherent in this, including a scene in which Lara shouts to her enemies that they don’t have to do this, and these beats are appreciated. But the sheer amount of death is staggering, and undermines the good writing that has come before it. It also harkens back to the fantasy of power that Lara embodied in the earlier games.

More strikingly, Tomb Raider suffers from a case of cognitive dissonance when it comes to the combat. It is spectacularly violent at times, including some kills with an ice-axe that are utterly brutal. The regularity of this violence badly undermines the vulnerability of Lara. She moves from being tearfully distraught at her first kill to gunning down seventy or more people just a few hours later. There are some wonderful moments inherent in this, including a scene in which Lara shouts to her enemies that they don’t have to do this, and these beats are appreciated. But the sheer amount of death is staggering, and undermines the good writing that has come before it. It also harkens back to the fantasy of power that Lara embodied in the earlier games.

There is a debate about whether the new game objectifies Lara as a vulnerable young woman to be protected rather than as a capable heroine the player can support. There was also a fierce pre-launch debate over the potential portrayal of sexual violence. Crucially, both these conversations are about Lara, the character, and not about the gameplay elements. It is a higher level of debate than the games would have supported before.

The old Lara Croft was a non-character, and Tomb Raider 2013 can hardly betray something that never existed. By choosing to reduce the player’s interaction at certain moments, Crystal Dynamics have managed to create something new. For the first time I’ve encountered in a Tomb Raider game, Lara is a worthy companion for the player, not just a blank slate onto which they can project their own desires. She is, in fact, her own woman. This is how it should be, and I love the new Lara.

… But they totally ripped off Neil Marshall’s The Descent (2005).