Welcome back to Random Encounter, the monthly digest of gaming’s hot topics. This month, Olivia Cottrell wants to know where all the good scripts have gone.

Last week, I had a very strange moment. I was sitting in my living room, controller in hand, and I cried. Not big, dramatic sobs, just a sudden overflow of emotion that left me scrabbling around for a tissue. This was not prompted by anything melodramatic. All the game had done was build a character up through interactions and dialogue, then scripted something for them to say that touched me in a way that only a few things ever have. This had never happened to me in a video game before – but perhaps I should have seen it coming.

Gaming has recently developed a trend towards titles that are, if not exactly heart-stopping works of literature, at least significantly more led by their writing. While this is hardly a new thing (I certainly never played Monkey Island for the puzzles) it is becoming more widespread. However, game companies have been slow to react to this shift, preferring to sell their games on the traditional points of graphics and gameplay. The current fan backlash against the unsatisfying ending of Mass Effect 3 has as much to do with fans’ criticism of the writing as it does with their feeling of betrayal by a company they feel is pursuing blockbuster status.

Why is writing so important? Firstly, games are, and have always been, storytelling experiences, no matter the strength of the actual narrative. We all have those ‘do you remember the time’ stories from games we loved – the time I got arrested in Skyrim for accidentally killing a chicken by shouting at it, the time I flipped a tank over a bridge in Halo, the infiltrator I met in Mass Effect 3’s multiplayer who was so stealthy she snuck right through the map… Tales we retell that enrich our gaming experience. It’s always been a part of nerd culture to relate these experiences, and they form a large part of how we relate to the game. Where there is bad or minimal narrative we will inevitably invent our own, even if it’s to cast our player avatar as a critic of the world that surrounds them. Who, upon facing a particularly terrible in-game moment, hasn’t imagined their avatar throwing their hands up in despair or giving their commander the side-eye? Players cannot help but impose some kind of narrative upon the game.

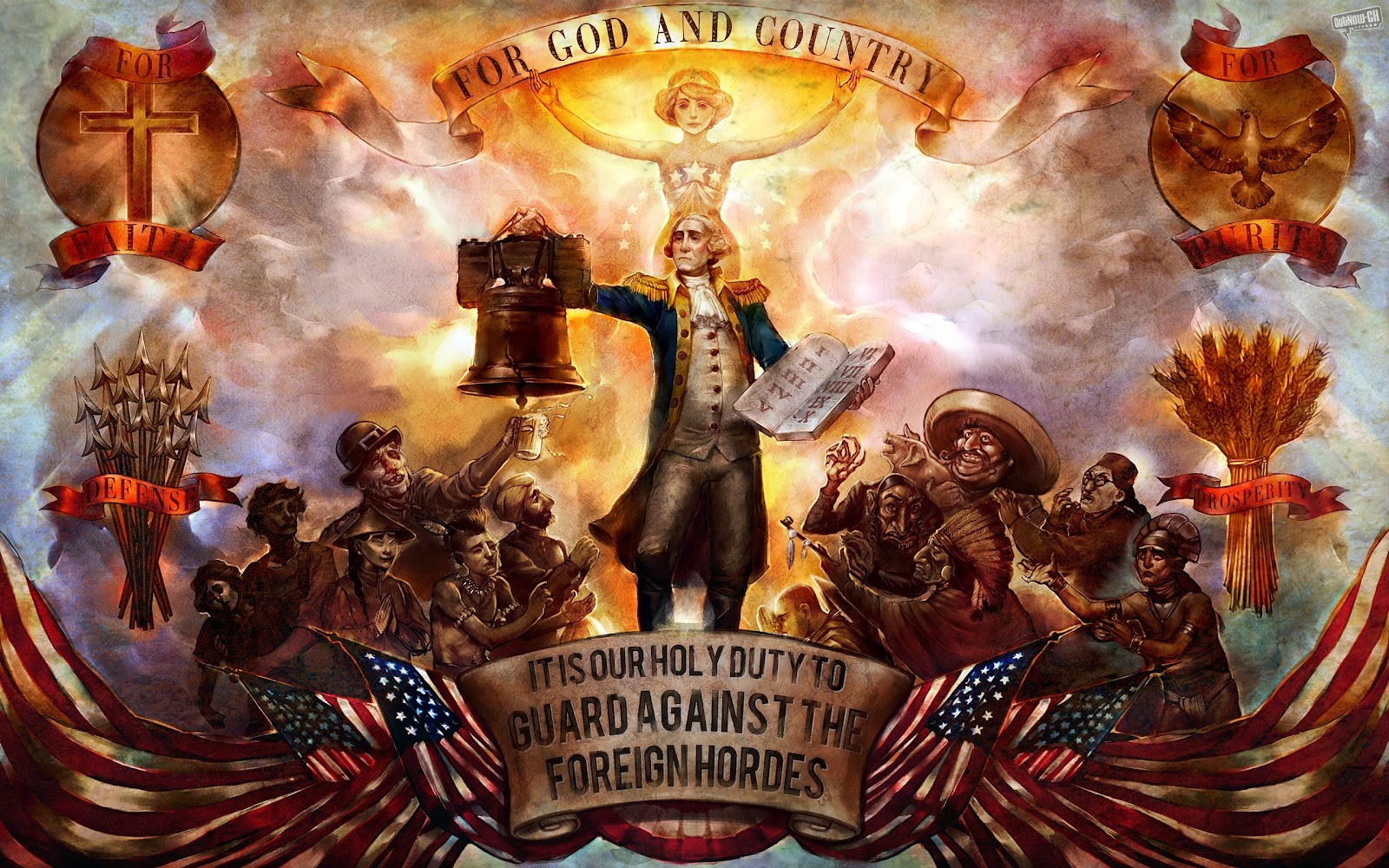

Secondly, when the game’s writing sings, it really adds to the experience. Take Dragon Age 2, for example. In many respects this was an extremely flawed title, whose technical development really suffered as it was rushed onto shelves. But the writing elevated the experience to something far beyond the previous Dragon Age game. My character met some amazing people, took part in a very different kind of fantasy story and, faced with no clear moral path, had to make some very questionable choices. The game’s setting, the city of Kirkwall, lived and breathed in its writing, and came alive through the game’s use of narrative and dialogue. Other titles, too, would be hollow without their writing. Uncharted, for example, is simply the very best action movie out there – without the strength of Nathan Drake’s character and the pure fun of the story and dialogue, it would simply be a pretty but dull shoot-em-up. Bioshock’s story elevated the underwater, art deco setting from novel to compelling. The company, recognising this, has applied the same storytelling concepts to a new location, foregrounding the importance of ideas over brand recognition.

But games companies refuse to acknowledge this. Perhaps because the public perception of the average gaming fan is still so far from the reality (we’re not all sweaty teenaged boy shouting down our team mates on Modern Warfare) or perhaps because quality writing is harder to quantify than decent graphics or good gameplay. Far too often games with good stories are sold out in favour of making the next flashy thing instead of delivering a rich and satisfying experience to the player. This completely ignores the investment and desires of the fans and undermines the ongoing quest of games as a whole to be recognised as a legitimate art form.

As gaming becomes a more successful industry, companies will have to ask themselves what kind of titles they wish to make and what they are willing to sacrifice in pursuit of quick profits. These days, games often tell great stories: but sometimes that story is woefully incomplete.

Tell us what you make of Olivia’s conclusions on our Facebook page or in the comments section below.